A version of this article first appeared in the October 4, 2019 Epoch Times.

Conscientious citizens know that impeachment of a president—any president—is a sad occasion. It is not a time for the unseemly enthusiasm now displayed by many in politics and the media.

Some cynics claim impeachment procedures are a free-for-all, determined by nothing but politics. That is not true. The Constitution and governing precedent impose rules. Those rules govern both impeachment (accusation) by the House of Representatives and trial in the Senate. Because most Americans understand the seriousness of impeachment-and-trial, they will insist that the rules be followed, even if the courts do not enforce them.

The Constitution’s framers modeled its impeachment-and-trial provisions on 18th century English practice. That practice rested largely on cases dating back to the 1300s. Since the Constitution was adopted, Congress has created more precedents. The Constitution and the precedents define the law of impeachment.

Under impeachment law, the House of Representatives may not constitutionally impeach a president—and the Senate may not constitutionally remove him—merely because they think his policies are misguided or harmful. They may not impeach or remove him because they don’t like his rhetoric. Or because he tweets too much. Or because he paid hush money to a prostitute while he was still a private citizen. Or because he fired someone they don’t think should have been fired. Or because (like every president for the first 185 years of the republic) he didn’t release his tax returns. Or because his party lost a certain number of seats in Congress.

Nor may they impeach or remove because the president owns shares in businesses that, in the course of ordinary market transactions, sell to foreign governments. Or because he is “the worse president ever”—the lament of every incumbent’s opponents. Despite assertions by Rep. Al Green (D.-Tex), they may not impeach or remove a president to stop him from being re-elected.

We do not have a parliamentary form of government where the legislature controls the executive. The president is independent of Congress. He is elected for a fixed term and is responsible to the people directly. To protect the president’s independence, Constitution narrows the grounds for impeachment to commission of (1) a felony (“Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes”) or (2) “high . . . Misdemeanors.”

Some claim the phrase “high misdemeanors” means whatever Congress wants it to mean. They are wrong. If it were true, the Constitution’s framers would not have listed grounds for impeachment. They would have let Congress choose whatever grounds it wished. If Congress could impeach and remove for any reason, the president would be a prime minister, dependent on the whims of the legislature.

Historical research shows that “high misdemeanor” means a breach of fiduciary duty—or as the Founders phrased it, a “breach of trust.”

Differences in legal terminology aside, a breach of fiduciary duty is much the same today as it was when the Constitution was adopted. Fiduciary duties are the legal obligations binding those who handle other people’s affairs: trustees, bankers, accountants, corporate executives, and so on. Breaches of fiduciary duty include failing to produce legally-required reports, neglecting one’s job, or doing the job incompetently, disloyally, or dishonestly.

Some critics say President Trump has breached his fiduciary duties. They claim he plays fast and loose with the truth, has lapses in competence, and in his discussion with the Ukrainian president tried to use his official influence to attack a political opponent. All this sounds bad.

Yet is also true that the level of conduct expected of politicians is significantly lower than that expected of private-sector fiduciaries. Politics is a notoriously dishonest and sloppy business, and successful politicians—even presidents—often say and do things that would send bankers or corporate executives to jail.

Fiduciary law tells us that when assessing an official’s conduct, we should consider how other people in similar positions comport themselves. Thus, when deciding whether a politician’s actions are impeachable, we must compare his conduct to that of other politicians. When weighing whether to impeach a sitting president, we consider how other presidents have acted.

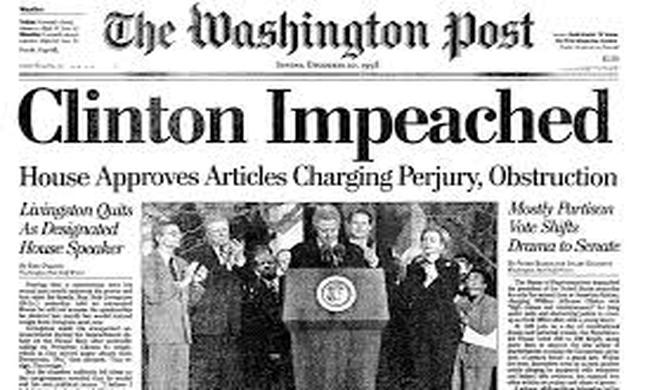

It is regrettable but true that many Presidents have routinely played fast and loose with the truth, acted incompetently, and used their office to attack political opponents. We are more aware of Trump’s faults, real and alleged, simply because of differences in treatment by the dominant media and other opinion-molders. In a different media environment, for example, John Kennedy’s conversion of the White House into a brothel, or Lyndon Johnson’s weaponizing of the FBI, or Barack Obama’s flagrant lies about the Affordable Care Act could have been the scandal of the century. Yet of all recent presidents, only Bill Clinton was impeached. And the Senate judged that even his commission of a felony—perjury in a court proceeding—did not justify removal from office.

Yes, the standards of conduct for federal politicians are ridiculously low. But impeachment proceedings must follow due process. Changing the rules retroactively violates due process. President Trump must be measured by the same standards that governed his predecessors.

The Constitution and impeachment precedent lay down rules to protect due process. Before the trial, Senators must swear that they will “do impartial justice according to the Constitution and laws: so help me God.” No other Senate proceeding requires a special oath like this. Even if God does not make an obviously biased Senator immediately accountable, the American people can do so.

The trial is governed by standing Senate rules that ensure due process. Precedent mandates that prosecutors prove their charges by “clear and convincing evidence.” The Constitution says that to convict, two thirds of Senators present (not a majority) must agree.

The Founders anticipated that unscrupulous Senators might try to pervert the trial of a president into lynch mob or a political circus. So the Constitution requires that when the president is tried, the Chief Justice of the United States—not the vice president or any Senator—presides.

In sum, the impeachment-and-removal process should not be a mere vent for political disagreements or partisan animosity. It a sad and serious procedure, governed by rules of law central to our system of justice.