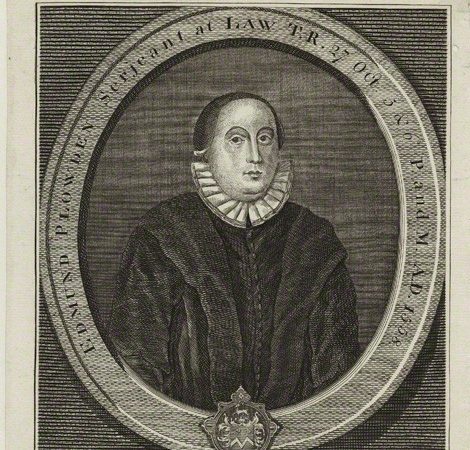

Above: Edmund Plowden in 1558—an English scholar who refined “originalist” methods of interpretation.

The New Yorker recently published an article by a law professor and CNN commentator that purported to critique originalism—the view that the Constitution means what the ratifiers understood it to mean. But like many attacks against originalism, it assailed a cartoon version rather than the real thing.

I knew it was almost certainly a waste of time to write a response—or more precisely a correction. Judging by the number of attacks on originalism and originalists in the New Yorker, it was clear the editors were not interested in exposing their readers to the other side. Nevertheless, I did pen a response—and of course they did not print it. For the record, here it is:

Dear Editor:

Critics of constitutional “originalism” often argue against straw versions of originalism rather than the real thing. This is certainly true of Jeffrey Toobin’s recent article on the subject.

A definition of originalism is not to be found in a casual remark by the late Justice Scalia, however venerated he was. More accurately defined, originalism is interpreting the Constitution according to its meaning to those who adopted it.

There is nothing extraordinary about this. Originalism has been the prevailing method of documentary interpretation in English and American law for at least five centuries: A statute is construed according to the “intent of the legislators.” A will is construed according “the intent of the testator.” A constitution is interpreted according to how it was understood by those who adopted it. In each case, we recover the meaning by examining the document’s words in light of previous and contemporaneous circumstances.

Here are Professor Tooley’s oversimplications:

* He states that “originalism presumes we can even figure out what the Framers thought about issues they never contemplated.”

Actually, the relevant understanding is that of the ratifiers, not of the framers. And we don’t don’t infer their “thoughts about issues they never contemplated.” Rather, we deduce the scope and definitions of their language. If we know their definition of “Commerce,” for example, it is irrelevant whether they foresaw commercial jet travel.

* Professor Tooley states that “the opposing school to originalism is one based on a ‘living’ Constitution, one whose meaning evolves with the society it presumes to govern.” This is an oversimplication because there is no single invented alternative to originalism, but many. “Interpretive theories,” as law professors call them, multiply according to the political and legal agendas of their proponents. People who would never think of re-writing a statute or a contract suddenly forget their scruples when the Constitution is concerned.

* Professor Tooley assumes that there is necessary opposition between “living” and “enduring” interpretation. But that opposition really depends on the constitutional clause one is construing. The drafters wrote some rigid clauses (e.g., the president’s four year term). But they also composed “evolving” clauses (e.g., the criteria for suspension of habeas corpus), and clauses somewhere in between (e.g., the Necessary and Proper Clause). The opposition is not between evolution or rigidity. It is between (1) originalists who apply the document’s meaning and (2) results-oriented advocates who want to change whatever meanings they don’t like.

* Professor Toobin writes, “[I]t’s chilling to consider that we might be bound forever not only to the words but to the world views of a group of eighteenth-century men—many of whom were slaveholders. That, however, is what originalism demands.”

This caricature is based on several factual errors. First, among the delegates to the state ratifying conventions who ratified the document and insisted on a Bill of Rights, the proportion of slaveholders was relatively small. It was even smaller among those who elected them.

As for “world views:” A Republican judge applying a law enacted by a Democratic Congress is not bound by their world views but only by their language. Similarly, although the Founders’ world views occasionally assist us in determining the meaning of a constitutional provision, ultimately it is the language that governs.

Nor are we “bound forever.” The Constitution contains an amendment process that Professor Tooley does not mention. Originalists do not question anyone’s prerogative to convince the American people we need constitutional change. We object only to evading that process through sophistry and constitutional legerdemain.

Sincerely,

Robert G. Natelson

Prof. of Law (ret.), The University of Montana

Senior Fellow in Constitutional Jurisprudence,

The Independence Institute