Scholars working on the Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution are approaching the end of the project they began in the 1970s, yet they continue to publish new material.

They have just issued three new volumes of ratification-era papers from Pennsylvania. These papers formerly were available only in microfiche format, a form researchers found very difficult to work with. But in the new indexed hard copy they are easy to read; I was able to scan all three volumes in just a few days. In this and several succeeding posts, I’ll summarize the highlights—just as I did last year, when volumes were issued for New Hampshire, South Carolina, and Vermont.

The new Pennsylvania volumes contain nothing that require me to revise the major conclusions in my book, The Original Constitution: What It Actually Said and Meant. In fact, they generally strengthen previous conclusions, while offering some additional insights.

Let’s begin with what is probably the most important contribution of these volumes: Reprinting four newspaper essays by Tench Coxe, urging ratification of the Constitution.

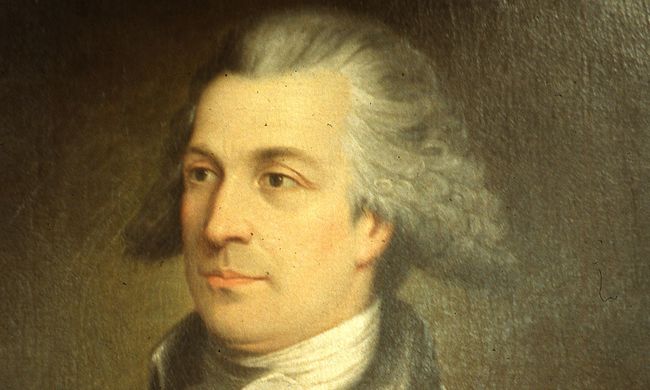

Coxe was a Pennsylvania businessman and economist who served in the last (1789) Confederation Congress. He later became Alexander Hamilton’s assistant secretary of the treasury. During the ratification era (1787-90), he was among the most widely-read pro-Constitution writers: Like The Federalist Papers, Coxe’s writings helped mold public understanding of the Constitution’s meaning. Unlike The Federalist, however, Coxe’s essays were written in direct, easy-to-read language. Newspapers around the country printed and reprinted them.

Perhaps Coxe’s most important contribution was disproving the claim made then by anti-federalists (and now by liberal constitutional commentators) that the Constitution creates a central government of nearly unlimited power. In several papers, Coxe listed many specific functions over which the states would retain exclusive jurisdiction.

Previously, we had access to essays Coxe composed under the pseudonyms “One of the People,” “An American Citizen,” and “A Freeman,”—as well as an essay he wrote in June, 1788 as “A Pennsylvanian.” One of the newly issued volumes adds four more to the public store, all signed “A Pennsylvanian.”

In the first two, Coxe pointed out that all the delegates to the Pennsylvania ratifying convention who opposed to the new federal Constitution were strong supporters of the controversial Pennsylvania state constitution. He contrasted this with the more bipartisan cast of those favoring the new federal constitution. Coxe sought to establish that Pennsylvania’s anti-federalists were narrow partisans who clung to a defective state charter.

In the fourth essay, he addressed some of the opponents’ arguments about the structure of the new government. More importantly, however, in both the third and fourth essays he rebutted the crux of the anti-federalist case—that the new federal Constitution gave the central government too much power. Thus, in the fourth essay, he contended that only the states, not the central government, would have any control over religion. And in the third essay he itemized many other functions outside the federal sphere—perhaps the longest of any of the lists he provided anywhere.

Coxe’s listing helped cement in the public mind the most natural meaning of the text: The Constitution created a strictly limited central government, which (outside the District of Columbia and the territories) had no authority over most aspects of American life. Coxe’s work demonstrates clearly that the current bloated federal government was not what the American people agreed to when they ratified the Constitution—in other words, that many of the current federal activities are simply illegitimate.

Here are Coxe’s actual words. The italics are his.

The legislature of each state must possess, exclusively of Congress, many powers, which the latter can never exercise. The state governments can prescribe the various punishments that shall be inflicted for disorders, riots, assaults, larcenies, bigamy, arson, burglaries, murders, state treason, and many other offences against their peace and dignity, which, being in no way subjected to the jurisdiction of the foederal legislature, would go unpunished. They alone can promote the improvement of the country by general roads, canals, bridges, clearing rivers, erecting ferries, building state houses, town halls, court houses, market houses,county gaols [jails—ed.], poor houses, places of worship, state and county schools and hospitals. They alone are the conservators of the reputation of their respective states in foreign countries, by having the entire regulation of inspecting exports. They can create new state offices, and abolish old ones; regulate descents of lands, and the distribution of the other property of persons dying intestate; provide for calling out the militia, for any purpose within the state; prescribe the qualifications of electors of the state, and even of the foederal representatives; make donations of lands; erect new state courts; incorporate societies for the purposes of religion, learning, policy or profit; erect counties, cities, towns and boroughs; divide an extensive territory into two governments; declare what offences shall be impeachable in the states, and the pains and penalties that shall be consequent on conviction; and elect the foederal senators. These things and many more can always be done by the state legislatures. How then can it be said, that they will be absorbed by the Congress, who can interfere in few or none of those matters, though they are absolutely necessary to the preservation of society and the existence of both the foederal and state governments.

In the executive department we may observe, the states alone can appoint the militia and civil officers, and commission the same. They alone can execute the state laws in civil or criminal matters, commence prosecutions, order out the militia on any commotion within the state, collect state taxes, duties and excises, grant patents, receive the rents and other revenues within the state, pay or receive money from Congress, grant pardons, issue writs, licences & c. [etc.—ed.]among their own citizens; or, in short, execute any other matter which we have seen the state legislature can order or enact. In the judicial department every matter or thing, civil or criminal, great or small, must be heard and determined by the state officers, provided the parties contending and the matter in question be within the jurisdiction of the state. Hence our petit and grand juries, justices of the peace and quorum, judges of the common pleas, our board of property, our judges of oyer and terminer, of the supreme courts, of the courts of appeal, or chancery, will all exercise their several judicial powers, exclusive and independent of the controul or interference of the foederal government.