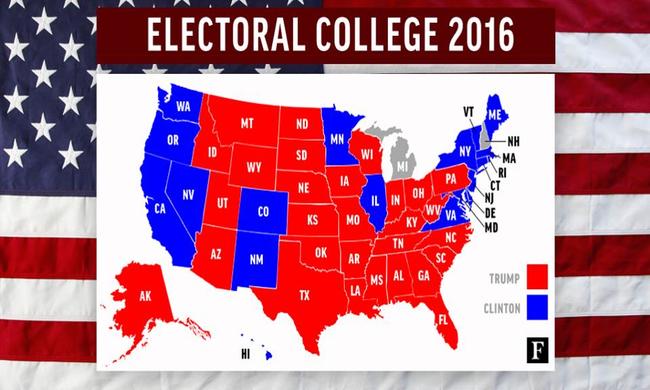

Colorado went Democrat in the last presidential election. But three of those elected as presidential electors wanted to vote for someone other than Hillary Clinton. Two eventually cast ballots for Clinton under court order, while one—now a party to court proceedings—opted for Ohio Governor John Kasich, a Republican. After this “Hamilton elector” voted, state officials voided his ballot and removed him from office. The other electors chose someone more compliant to replace him.

Litigation over the issue still continues, and is likely to reach the U.S. Supreme Court. Moreover, President Trump’s victory in the Electoral College, despite losing the popular vote, remains controversial. So it seems like a good time to explore what the Electoral College is, the reasons for it, and the Constitution’s rules governing it. This is the first of a series of posts on the subject.

The delegates to the 1787 constitutional convention found the question of how to choose the federal executive one of the most perplexing they faced. People who want to abolish the Electoral College usually are unfamiliar with how perplexing the issue was—and still is.

Here are some of the factors the framers had to consider:

* Most people never meet any candidates for president. They have very little knowledge of the candidates’ personal qualities. The framers recognized this especially would be a problem for voters considering candidates from other states. In a sense, this is less of a concern today because, unlike in 1787, we have mass media through which candidates can speak directly the voters. In other ways, however, it is more of a concern than it was in 1787. Our greater population renders it even less likely for any particular voter to be personally familiar with any of the candidates. And, as I can testify from personal experience, mass media presentations of a candidate may be 180 degrees opposite from the truth. One example: media portrayal of President Ford as a physically-clumsy oaf. In fact, Ford had been an all star athlete who remained physically active and graceful well into old age.

* Voters in large states might dominate the process by voting only for candidate from their own states.

* Generally speaking, the members of Congress would be in a much better position to assess potential candidates than the average voter. And early proposals at the convention provided that Congress would elect the president. However, it is important for the executive to remain independent of Congress—otherwise our system would evolve into something like a parliamentary one rather than a government of three equal branches. More on this below.

* Direct election would ensure presidential independence of Congress—but then you have the knowledge problem itemized above. In addition, there were (and are) all sorts of other difficulties associated with direct election. They include (1) the potential of a few urban states dictating the results, (2) greatly increased incentives to electoral corruption (because bogus or “lost” votes can swing the entire election, not just a single state), (3) the possibility of extended recounts delaying inauguration for months, and (4) various other problems, such as the tendency of such a system to punish states that responsibly enforce voter qualifications (because of their reduced voter totals) while benefiting states that drive unqualified people to the polls.

* To ensure independence from Congress, advocates of congressional election suggested choosing the president for only a single term of six or seven years. Yet this was only a partial solution. Someone elected by Congress may well feel beholden to Congress. And as some Founders pointed out, a president ineligible for re-election still might cater to Congress simply because he hopes to re-enter that assembly once he leaves leaves office. Moreover, being eligible for re-election can be a good thing because it can be an incentive to do a diligent job. Finally, if a president turns out to be ineffective it’s best to get rid of him sooner than six or seven years.

* Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts suggested election by the state governors. Others suggested election by state legislatures. However, these proposals could make the president beholden to state officials.

* The framers also considered election of the president by electors elected by the people on a strict population basis. Unless the Electoral College were very large, however, this would require electoral districts that combined states and/or cut across state lines. In that event, state law could not effectively regulate the process. Regulation would fall to Congress, thereby empowering Congress to manipulate presidential elections.

* In addition to the foregoing, the framers had to weigh whether a candidate should need a majority of the votes to win or only a plurality. If a majority, then you have to answer the question, “What happens if no candidate wins a majority?”On the other hand, requiring only a plurality might result in election of an overwhelmingly unpopular candidate—one who could never unite the country. The prospect of winning by plurality would encourage extreme candidates to run with enthusiastic, but relatively narrow, bases of support. (Think of the possibility of a candidate winning the presidency with 23% of the vote, as happened in the Philippines in 1992.)

The delegates wrestled with issues such as these over a period of months. Finally, the convention handed the question to a committee of eleven delegates—one delegate from each state then participating in the convention. It was chaired by David Brearly, then serving as Chief Justice of the New Jersey Supreme Court. The committee consisted of some of the most brilliant men from a brilliant convention. James Madison of Virginia was on the committee, as was John Dickinson of Delaware, Gouverneur Morris of Pennsylvania, and Roger Sherman of Connecticut, to name only four of the best known.

Justice Brearly’s “committee of eleven” (also called the “committee on postponed matters”) worked out the basics: The president would be chosen by electors appointed from each state by a method determined by the state legislature. It would take a majority to win. If no one received a majority, the Senate (later changed to the House) would resolve the election.

Next time: Rules governing the Electoral College.