This essay was first published in the May 19, 2024 Epoch Times.

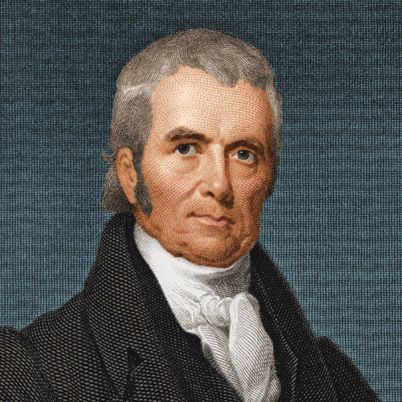

The first installment in this series described Chief Justice John Marshall’s early life and his contributions to the ratification of the Constitution. This Part 2 examines his continuing career: his service as envoy to the French government during the infamous XYZ affair and his short tenures in Congress and as Secretary of State.

After the Constitution was ratified, Marshall resumed his Richmond law practice, Some biographers suggest that he served only occasional terms in the state legislature, but the website of the Virginia House of Delegates shows him as continuously in the House from 1782 until 1798. By 1795 he had become the unofficial head of the Federalist Party in Virginia.

The XYZ Affair

President George Washington—who from time to time had benefitted from Marshall’s legal advice and whose administration Marshall stoutly defended—offered him the positions of Attorney General, Minister to France, and (apparently) associate justice of the Supreme Court. Marshall declined them all. Being from a family of modest means, he had to pursue his law practice to secure his financial future.

However, in 1797 he accepted President John Adams’ nomination as one of three envoys to France. His two colleagues were Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney of South Carolina—both former Constitutional Convention delegates. The three arrived in Paris in October of the same year and presented their credentials to the French foreign minister, Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand.

Except for some initial formalities, Talleyrand refused to deal directly with them. Instead, he sent four subordinates, designated in the papers subsequently released to the public as W, X, Y, and Z. “W” played only a small part in the subsequent events, which became known as the XYZ Affair.

On the pretense of being offended by some passages in a speech by President Adams, the French demanded a “softening” remedy: This remedy was “money, a great deal of money.” X, Y, and Z told the Americans they must pay cash to French officials, including Talleyrand himself. Moreover, they must arrange for the United States to give a large loan to the French government.

The three Americans were outraged. They had a right to be: Modern accounts of the affair are bad enough, but they do not begin to capture the insulting nature of the repeated French demands. For readers who want to examine the sordid record for themselves, I’ve posted here a rare 1798 reproduction of the envoys’ dispatches, written mostly by Marshall.

The dispatches report how the envoys responded. Following is one of their conversations with “X:”

M[onsieur] X. again returned to the subject of money. Said he, “Gentlemen, you do not speak to the point—it is money: it is expected that you will offer money.”

We said we had spoken to that point very explicitly: we had given an answer.

“No, said he, “you have not; what is your answer?”

We replied, “It is no; no; not a sixpence.”

Marshall and Pinckney returned home in disgust. Gerry remained in Paris in the hope French attitudes would change.

When, at the request of Congress, President Adams released the envoys’ dispatches to the American public. Marshall became a national hero.

Congress and the Speech on International Law

In 1798, George Washington reached out from retirement to urge both Patrick Henry and John Marshall to run for the House of Representatives as candidates of the Federalist Party. Both agreed to do so.

Virginia held its congressional elections late—on April 24, 1799. Henry won his seat, but died soon after. Marshall, riding in part on popularity gained in the XYZ affair, defeated Democratic-Republican incumbent John Clopton.

Marshall quickly became a leader among the Federalist forces in the House of Representatives.

His most notable achievement during his time in Congress was a speech on Mar. 7, 1800, delivered in defense of President Adams. The topic was international law, and the speech not only accomplished its immediate purpose, but helped cement the position of the president as America’s chief representative in foreign affairs.

The background was this: Thomas Nash (alias Jonathan Robbins) committed a murder on a British warship. Claiming to be an American impressed into British naval service, Nash subsequently fled to the United States. President Adams was not convinced by Nash’s claim of American citizenship. In compliance with America’s treaty with Great Britain, the president extradited him to England for trial.

The president’s opponents in Congress proposed a resolution to condemn him for this decision. Marshall’s speech stated the case against this resolution.

Marshall pointed out that by international law a ship was considered part of the territory of the country commissioning it. The ship on which Nash had committed the murder was British. For this reason, only Britain, not the United States, had jurisdiction over the crime.

Marshall conceded that piracy was an exception to this rule. By international law, a pirate was hostis humani generis—an “enemy of the human race.” Therefore, all nations had jurisdiction over his crimes. But Nash, although a murderer, was not a pirate. Only the British had jurisdiction over him.

The president’s opponents argued that Adams should have presented the issue to a court. But Marshall responded that some questions of law are properly decided elsewhere. The president was the country’s primary representative in foreign affairs, and it was part of his job to decide legal issues arising under treaties.

Marshall’s deft treatment of international law issues helped defeat the condemnatory resolution, and it won the gratitude of President Adams.

Secretary of State

In May, 1800, President Adams appointed Marshall as Secretary of State. Marshall’s biographer Charles F. Hobson, writes: “Although he administered that department for less than a year, Marshall made a valuable contribution, most notably in forwarding negotiations with Great Britain concerning pre-Revolutionary debts owed to British subjects.”

Marshal also drafted the president’s annual message to Congress and acted as a confidential advisor.

After Oliver Ellsworth resigned as Chief Justice, the president nominated the Secretary of State to replace him. The Senate confirmed the nomination on Jan. 27, 1801.

* * *

In the next installment: Two landmark Supreme Court cases and the false “big government” narrative about Marshall.