Starting discussions about the role and effects of teachers unions certainly is one way of pouring cold water on a party or social event. A lot of the topics surrounding K-12 education policy and reform can be emotionally charged.

But if you want to step back from the heated discussions and consider what the research has to say… well, frankly, there isn’t a huge record to fall back on. If you remember back a couple years (when I was still 5), I shared about a new study that purported to draw a connection between higher teacher union dues collection and lower student proficiency.

At that time, I also highlighted the only two other known pieces of quality research that spoke to the question. Back in 2007, Dr. Terry Moe from Stanford found that at the local level, restrictive collective bargaining provisions negotiated by teachers unions “has a very negative impact on academic achievement,” especially among more challenging student populations.

Then there’s the ideal state-level laboratory test case of New Mexico, which Benjamin Lindy’s analysis for the Yale Law Journal demonstrated “mixed results from union bargaining power, better SAT scores but more poor kids dropping out of high school.”

Well, a new, rigorous state-level analysis reassures us that Colorado’s education labor terrain stands us in stronger stead to help students succeed than many other states do.

Writing for Education Next, Michael Lovenheim and Alexander Willen unpack the long-term effects of states that mandate school districts give unions local bargaining monopolies. Removing other factors from the equation, the authors reach some interesting conclusions about the impacts of going to school in a “duty-to-bargain” state:

We find no clear effects of collective-bargaining laws on how much schooling students ultimately complete. But our results show that laws requiring school districts to engage in collective bargaining with teachers unions lead students to be less successful in the labor market in adulthood. Students who spent all 12 years of grade school in a state with a duty-to-bargain law earned an average of $795 less per year and worked half an hour less per week as adults than students who were not exposed to collective-bargaining laws. They are 0.9 percentage points less likely to be employed and 0.8 percentage points less likely to be in the labor force. And those with jobs tend to work in lower-skilled occupations.

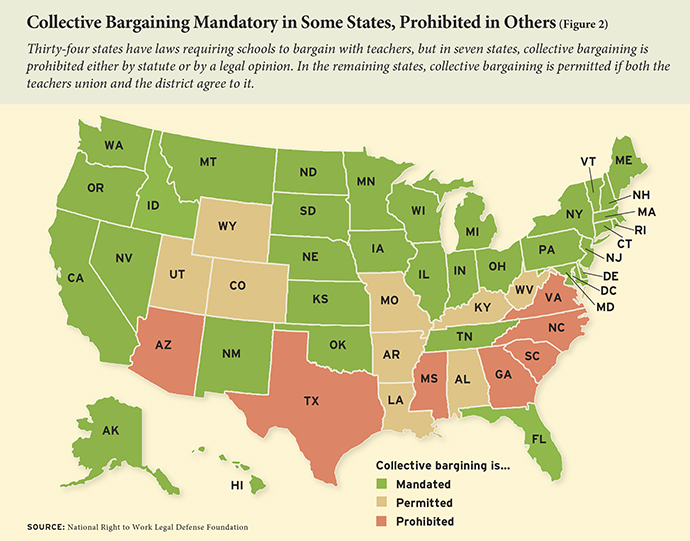

Using data from the National Right to Work Legal Foundation, Education Next displays the duty-to-bargain states in green below:

Seeing as how it’s Geography Awareness Week, I hope you were able to pick out that our own Colorado does not fit the bill. Instead, its peach (?) hue indicates that the Centennial State permits, but does not mandate, local collective bargaining. That’s always been the case, and hopefully continues. Fewer than 40 of the Centennial State’s 178 districts formally recognize union power.

What specifically is it about sweeping unionization laws that put a crimp on students’ future earnings? Is it indicative of a larger restrictive labor environment? Or does it follow along the lines of the 2013 report, and suggest the union lobbying power that accompanies mandated bargaining also tends to block reforms that might help students?

Honestly, I don’t know. The finer points of underlying causes still demands more research, as the National Council on Teacher Quality called for back in 2008.

What’s become increasingly apparent is that the impact of unions as currently constituted on education outcomes for students is not benign. While we are not led to a definitive series of policy solutions, the overall body of research does tell us that key labor reforms should be left on the table — along with a reminder that how they are implemented matters greatly.

During the recent Jeffco recall election debacle, opponents of reform frequently hurled back charges that the likes of me and my friends spent too much time harping on unions. Maybe? Maybe not. The impact of labor and unions on learning is far from everything, but it’s slowly becoming more and more clear that it does mean something.

If we’re serious about doing what’s right by students first, and less wedded to the benefits of certain adults and groups get from the system, then let’s keep following where the evidence leads.