Many Democratic lawmakers, climate activists, and progressive academics see so-called beneficial electrification as the wave of the future for climate action.

As such, there has been a growing chorus among this community in recent years calling for the end of natural gas heating systems and appliances and propping up their electric alternatives as superior options. Occasionally, even the media gets in on the action.

Earlier this week, the Colorado Sun joined in on that chorus by publishing a glowing profile of a Denver pizzeria that recently made the switch from gas cooking appliances to an all-electric oven:

Somewhere between sliding pie No. 19 into a waiting box, and nudging pie No. 20 six inches to the left in the 550-degree oven at Sexy Pizza, Angela Hilton touches a flour-dusted finger to a control panel and turbocharges the electrification movement.

Tweaking one button instantly cools a hot spot in Sexy Pizza’s 8-foot-wide, three-stack electric oven, far more effectively and efficiently than in the old natural gas pizza ovens that Hilton trained on. And in slinging 23 pies around the $55,000 oven on a Thursday morning using her forearms of steel, Hilton is a warrior in fighting climate change.

A deeper look beyond the imagery of a pizza peel-wielding warrior marching in Gaia’s army, however, reveals the real challenges that remain in making electrification a desirable option for the masses.

Electric appliances, at least those that can match the performance of gas alternatives, typically remain far more expensive to purchase and install than their methane-burning counterparts.

Meanwhile, government subsidies meant to balance the scales simply socialize their added costs among the tax base and remain cumbersome to obtain due to the ever-present slog of city bureaucracy. As the Sun article admits later in the piece:

Upfront expense is always a big question, Forlines said. New electric ovens and stoves with elaborate computerization are often pricier than comparable gas commercial models, just as electric vehicles can cost $10,000 more even after rebates, or a heat pump system seems exorbitant.

The city of Denver may offer rebates for restaurant electrification from its publicly voted climate resilience sales tax, but so far the paperwork has been daunting, Peters said.

However, the biggest drawback goes beyond upfront financial costs to include the economics of actually operating electric appliances. The fact remains that, under current market conditions, using electricity is generally more expensive than burning natural gas despite the former’s inherent efficiency advantages.

Just a few weeks into the latest oven experiment, Sexy Pizza may actually be spending more money on power at the Uptown stand than it does for gas ovens, Peters said. Natural gas is relatively cheap at the moment, away from any winter storm spikes, and electric costs have gone up.

According to the most recent available monthly price data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration, natural gas indeed remains significantly cheaper than electricity for commercial end-users in Colorado.

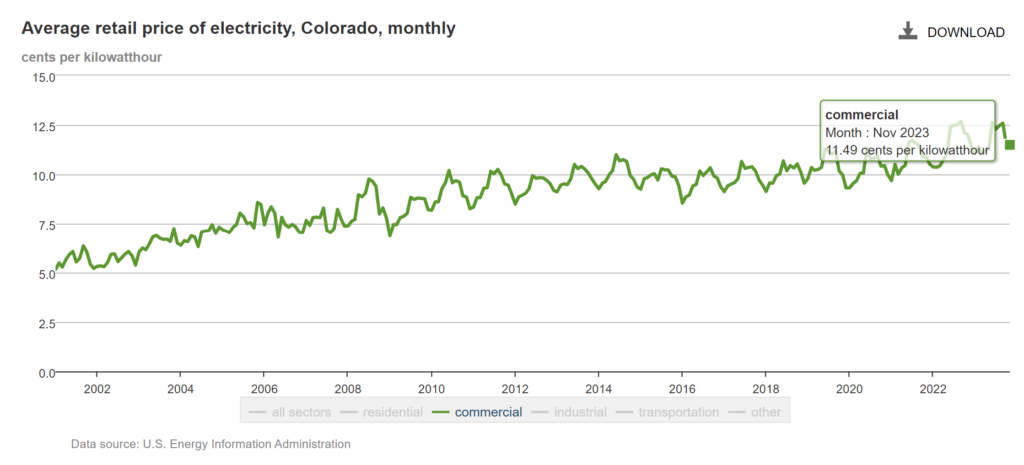

As of November 2023, commercial electricity customers in Colorado paid 11.7 cents per kilowatt hour (kWh) for electric service on average.

Source: US EIA Electric Power Monthly

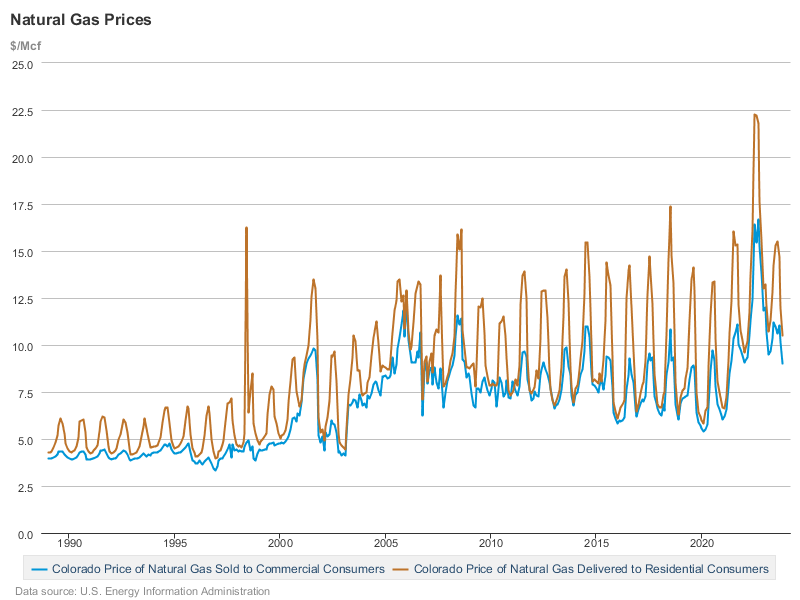

Meanwhile, commercial natural gas consumers paid $9.01 per thousand cubic feet (Mcf) on average that same month. A simple conversion of that amount from $/Mcf to cents/kWh yields a total of approximately 3 cents/kWh, making natural gas roughly four times cheaper on average per unit of energy produced for commercial customers in Colorado. The ratio is similar for residential natural gas and electricity costs.

Source: US EIA Monthly Natural Gas Data

Now, it is important to keep in mind that the pizzeria profiled by the Sun adopted electrification of its own volition. If a person places a greater weight on reducing their share of greenhouse gas contributions—however insignificant they may be in the grand scheme of things—over maximal cost effectiveness, more power to them. That should be any home or business owner’s right in a free society.

However, the rub lies in the fact that many policymakers in charge at both the state and local levels in Colorado no longer wish to allow consumers to make that choice voluntarily.

Case in point: the disparity in consumer expense between natural gas and electricity in Colorado hasn’t stopped climate activists from pushing for Denver Mayor Mike Johnston to fulfill his campaign pledge of banning all gas usage in the city’s new residential construction moving forward.

As reported in a sympathetic Denver Post article this week:

New restrictions on the use of natural gas to power some large buildings in Denver took effect in January, but it remains unclear when more rules about gas in single-family homes might be considered again.

During his campaign, Mayor Mike Johnston promised to ban gas hookups in new residential buildings — one of the key differences between his and his opponent’s climate platforms. If fulfilled, the new rule would mean all new homes would be powered solely by electricity, with no natural gas for heating, hot water or appliances — including for gas kitchen ovens and stoves.

The timeline for when such a policy might be pursued remains unclear.

The Post article quotes a spokesperson for Johnston’s Climate and Sustainability office as being notably non-committal about future plans for a residential gas ban, but it’s only a matter of time before the prevailing winds of progressive municipal governance force his hand.

The cities of Crested Butte and Lafayette have already moved to enact municipal natural gas bans, earning heaps of praise from climate activists in the process.

Meanwhile, the Denver City Council already came very close to enacting a residential natural gas ban in 2022 before ultimately punting on the question as an arctic cold front moved into the state that saw natural gas put up a heroic effort in buoying the state’s electric grid and home-heating needs.

So while the Johnston administration may dodge the question for now, you can be sure that the topic will return for serious consideration in the near future. And when it does, as the experience of the pizzeria demonstrates, residents of the state’s largest city can expect a sizeable bump in their monthly energy bills.

At least city leaders can say they meant well.