For an audio version read by the author, please click here.

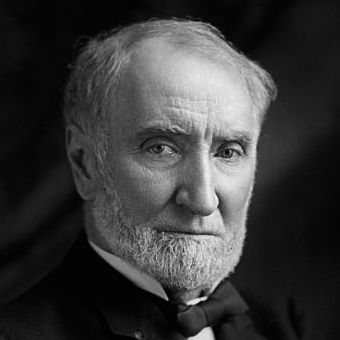

Above: Rep. Joe Cannon of Illinois was one of the most powerful Speakers ever.

This essay was first published in the Oct. 5, 2023 Epoch Times.

With the speakership of the U.S. House of Representatives in the news, it seems a good time to review the role of the speaker in our constitutional system.

The Speaker of the House is the presiding officer of the House of Representatives. The name of the position, like so much in our constitutional and legal tradition, derives from Great Britain: The presiding officer of the British House of Commons is also called the speaker.

By contrast, the presiding officer of the Senate is the vice president of the United States, whom the Constitution designates as president of the Senate. Thus, when the vice president opts to be in the chair, the Senate has no choice as to its presiding officer. However, the Senate chooses a president pro tempore to preside when, as very often occurs, the vice president is absent.

The Constitution states that the House “shall chuse [sic] their Speaker and other Officers.” (Article I, Section 2, Clause 5). The Constitution also gives the House power to adopt its own rules (Article I, Section 5, Clause 2). These rules fix the method of electing the speaker.

On occasion, the House has opted to elect its speaker by a simple plurality—that is, awarding the job to whomever obtains the most votes. Under that system, a person could be elected with only a minority of ballots if those ballots were spread out among three or more candidates. But the current rules provide for choice by a majority of those voting. That means if all 435 Representatives are present and cast ballots, to win a candidate must receive 218 votes. If only 400 Representatives vote, a candidate needs 201.

For most of our history, the United States has had a strong two-party system. One of the two parties almost always commands a majority in the House, and the members of that majority (if they stick together) determine who the speaker will be. If, however, a third party were to arise that holds the balance of power between the two major parties (as often happens in Europe), then the speaker would be elected by a coalition of parties with members sufficient to amount to a majority.

Speakers can have more or less power, depending on the House rules at the time, the speaker’s personality and political skills, and the political climate. At times in American history, powerful speakers have ruled like virtual dictators over the House, by using patronage and punishment to control its members. An example of a very powerful speaker was Joe Cannon (R-Ill.), who served in that office from 1903 to 1911.

The Constitution—specifically the 25th Amendment— creates a role for the Speaker beyond his duties in the House of Representatives. The amendment addresses the disability, resignation, and death of a president. It provides for formal notice if the president decides he is or will be unable to execute the functions of his office (as when, for example, he’s about to undergo an operation under general anesthesia). It also provides for notices if the vice president and a majority of the cabinet (or such other body determined by law) decide the president is incapable of performing the responsibilities of his office. It further mandates formal notices if the president contests the claim that he’s disabled. In each case, the Constitution designates two officers to receive those notices— the Senate’s president pro tempore and the speaker of the House.

The Constitution states that if the president is disabled, resigns, or dies, the vice president succeeds him. It also states that Congress may by law designate succeeding officers after the vice president.

The Presidential Succession Act of 1947 places the speaker in third position, after the president and vice president and just before the Senate president pro tempore (fourth) and the Secretary of State (fifth). However, the 25th Amendment provided a way for a new vice president to be appointed if the former vice president moves to the top job. (This procedure has been used twice.) Thus, the chances of the speaker becoming president are very small.

Although in prior years, the speaker has always been someone elected as a Representative, the Constitution doesn’t require this. The House could choose a person who has no elected position.

Trump for Speaker?

After President Joe Biden was declared the winner of the 2020 election over President Donald Trump, some disappointed Trump supporters spun a scenario whereby (1) the Republican House of Representatives chooses President Trump as its speaker, (2) the House impeaches both President Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris, (3) the Senate convicts them and removes them from office, and (4) President Trump ascends once again to the presidency. Of course, this scenario was fantasy: Representatives have no motivation to choose an outsider to lead them, and a Democratic Senate is highly unlikely to remove either President Biden or Ms. Harris from office.

Still, a few Republican Representatives are now saying they may support President Trump for speaker. Initial reports are that President Trump is ambivalent about it. Realistically, though, this idea is unlikely to get very far. Besides the natural unwillingness of lawmakers to choose someone to lead them who’s not a member of Congress, there is this factor: It would be hard for anyone to function as speaker who doesn’t have the deep familiarity with the practices, rules, and personalities of the House that only prior experience can bring.