This is the first of a five-part series on Founding Father John Dickinson, who published his highly influential “Farmer Letters” exactly 250 years ago. The series was first published by the Washington Post’s blog, The Volokh Conspiracy.

This is the first of a five-part series on Founding Father John Dickinson, who published his highly influential “Farmer Letters” exactly 250 years ago. The series was first published by the Washington Post’s blog, The Volokh Conspiracy.

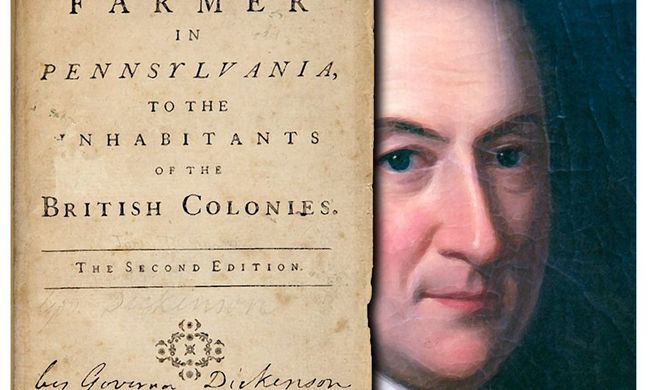

This year marks the 250th anniversary of one of the most influential series of writings in American history. The series was John Dickinson’s Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania. The “letters” were twelve newspaper essays, the first of which was published in November, 1767.

In accordance with the contemporaneous understanding of freedom of the press, Dickinson chose to remain anonymous: He signed the letters “A Farmer.” The letters argued that Parliament’s Townshend duties were improper and unconstitutional, and explained how Americans should resist them.

The Farmer took America by storm. The essays were widely reprinted individually, and they were collected as a book. There were editions in Britain and Europe. When Dickinson’s true identity emerged, he became the second most famous American in the world, after Benjamin Franklin.

This is the first of five postings on the life and thought of John Dickinson. In addition to examining The Farmer and other writings, these postings summarize how the author’s views affected the drafting and ratification of the U.S. Constitution.

John Dickinson was born in Maryland on November 8, 1732 to Samuel and Mary Cadwalader Dickinson. His father was a prosperous planter of tobacco, and later of wheat. In 1740 the family moved to Delaware, occupying a home near Dover. His parents valued learning and provided John and his few surviving siblings with an excellent classical education.

By 1750, John decided he wanted to be a lawyer, and that year he began clerking with the leading attorney in Philadelphia. In 1754, his parents sent him to London’s Middle Temple, where he studied for another three years. His correspondence with his parents from England still survives, displaying mature commentary on daily life and English political developments.

Thus, Dickinson received many advantages. But in London he encountered a severe obstacle: poor health. Even as a young man, he seems to be been subject to infection, and this remained true throughout his life. After age 40, he also suffered from gout.

In 1757, he was admitted to the bar at the Middle Temple and returned to America. Success in his Philadelphia law practice was rapid. Besides being bright and diligent, he seems to have had a magnetic presence. He was the kind of man people wanted to be around and wanted to entrust with their affairs.

Much of his Dickinson’s practice centered on private rather than public law: decedents’ estates, land claims, and most likely trusts. As was true of other founders, the rules prevailing in private law—particularly the rules binding fiduciaries—influenced Dickinson’s attitudes toward public law.

In those days Pennsylvania and Delaware were tied in harness (they had a common governor), so a young man of promise could aspire to a political career in both states. Before John was 27, he won a seat in the Delaware colonial assembly. He was re-elected the following year, and thereupon his colleagues in the assembly elected him Speaker. In 1762, he won a special election to fill a vacancy in the Pennsylvania house of assembly. He was re-elected in 1763 and 1764.

While serving in the Pennsylvania assembly he faced a political crisis. Dickinson had frequently been critical of the colony’s propriety charter with the Penn family. However, when Joseph Galloway and Benjamin Franklin—two of the colony’s most powerful figures—proposed to petition the king to convert it into a royal charter, Dickinson was skeptical. A royal charter, he believed, would leave Pennsylvania unprotected if the British government ever became oppressive.

On May 24, 1764 Dickinson rose in the assembly to deliver an elaborate speech in opposition to the petition. A written version of this oration survives. It was extraordinary for its careful balancing of the risks and rewards attributable to alternative courses of conduct. It was extraordinary also for use of what Dickinson’s beloved Roman authors called sententiae—sound bites. Among them:

* “Power is like the ocean; not easily admitting limits to be fixed in it.”

* “It will be much easier for me to bear the unmerited reflections of a mistaken zeal, than the just reproaches of a guilty mind.”

* “A good man ought to serve his country, even tho’ she resents his services.”

The speech identified the charter change as a constitutional alteration requiring special procedures to adopt. Dickinson maintained that a legislature elected under one constitution has no power to create another one. A new constitution required the “almost universal consent of the people.”

Although Dickinson overwhelmingly lost the Assembly vote, he was soon vindicated. The passage of the Stamp Act the following year demonstrated the correctness of his prediction that the British government might prove more oppressive than the Penn family. The charter change request died quietly.

In 1765, Pennsylvania sent Dickinson to the Stamp Act Congress in New York. His fellow commissioners (delegates) selected him to author the Congress’s chief pronouncement, the “Declaration of the Rights and Grievances of the Colonists.” Although Parliament soon repealed the Stamp Act, two years later Parliament replaced it with the Townshend Acts. That action provoked the Farmer letters.