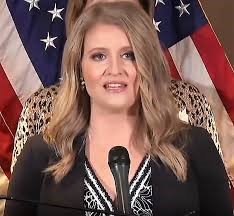

Above: Former Trump campaign attorney Jenna Ellis

For an audio version of this essay read by the author, please click here.

This essay first appeared in the October 25, 2023 Epoch Times.

Jenna Ellis, young attorney and formerly a Colorado Christian University professor, has pleaded guilty to a single count of “aiding and abetting false statements and writings.” She did so in a deal with prosecutors in the Georgia conspiracy case against former President Donald Trump and his campaign organization.

Ms. Ellis read an in-court statement presumably worked out with the prosecutors. She said she had failed to do “due diligence.” Why? Because she didn’t independently verify her superiors’ claims that the 2020 election had been corrupt.

But the standard she supposedly violated makes no sense. In the short time available for challenging the 2020 election, there was no way she should have—or even could have—made an independent investigation. In the absence of evidence her superiors were lying to her, her professional obligation was to rely on the information they gave her.

Associates employed by law firms, accounting firms, and other professional organizations routinely rely on information their superiors give them. Usually they have no choice: Relying on information your co-workers give you is required both by everyday practicalities and your duty to the firm. This was Ms. Ellis’s situation when she worked for the Trump team challenging the claimed election results.

Media Myths

To understand why this is so, let’s first clear away some myths propagated by the left-leaning media:

Media myth #1: “There were no serious irregularities in the 2020 popular vote.”

Reality: The media were making this claim almost immediately in the wake of the popular vote, and before any objective investigation was possible.

I don’t know if there was much actual fraud. But other irregularities included (1) the decision of many states to conduct their elections in a way that violated federal law and benefited the Biden campaign, (2) widespread and improper intervention by left-leaning non-profits in election administration (the “Zuckerbucks” issue), and (3) alteration of election procedures in some swing states by courts and executive officials, despite the U.S. Constitution’s commitment of presidential election procedures to the state legislatures.

We may never know whether these irregularities swung the election. But Ms. Ellis, like other members of the Trump team, had reasons to be suspicious.

Media myth #2: “The failure of the Trump lawsuits shows the election was clean.”

Reality: This claim ignores the extremely high standards of proof required in election-challenge lawsuits. More importantly, it disregards that nearly all those suits were dismissed on procedural grounds (usually standing), not on the merits.

Media myth #3: “The Ellis guilty plea is more proof that there was never any evidence of serious irregularities in the 2020 election.”

Reality: The plea more likely represents the effort of a young professional woman to avoid more damaging publicity, to forestall the (probably remote) threat of jail time, and to get on with her life.

Ellis and the Trump Team

Let us stipulate that during the 2020 election contest, Ms. Ellis—like the rest of the Trump legal team—was in over her head. Nor was she guiltless: She had billed herself as a constitutional law expert, although she had relatively little background in the subject. Indeed, with the notable exception of professor John Eastman (a genuine constitutional scholar), the team lacked the constitutional and election law expertise necessary for the job. As I pointed out in early 2021, one of their many mistakes was wasting time bringing lawsuits instead of appealing to the legislatures of the contested states.

One might have thought the president of the United States would have been better served.

On the other hand, it’s absurd to claim that Ms. Ellis should have—or could have—independently verified whether there was fraud in the 2020 election. She was a subordinate lawyer given information by senior lawyers of good standing. She had every right to believe them because, as far as I can see, she had no independent evidence they were lying; on the contrary, as pointed out above, she had reason to suspect the announced election results.

Moreover, she was working within a very tight time frame, and had no time or resources to conduct her own investigation.

In those circumstances, her duty to her client required her to act on what she had been told, and not to spend time and resources second-guessing.

When Should a Young Professional Speak Up?

To be sure, there are times when a young associate professional should doubt his or her superiors. Early in my legal career, I came across documentary evidence that another member of my firm may have lied on an affidavit. I brought the case to my superior’s attention, and his failure to respond appropriately was one reason I quit the firm.

But in my case, the evidence was documentary, and my doubts were based on months of experience with similar documents.

However, the statement Ms. Ellis read as part of her plea bargain suggests that a professional employee must second guess his or her bosses at every turn. The employee must do so even if he or she has no objective reason for thinking they might be lying. That is an impossible and unethical standard.

Fortunately, no one outside the Trump conspiracy case is likely to take that standard seriously. But if it is taken seriously, it will send a chill down the spine of every employed professional in the country.