by Linda Gorman

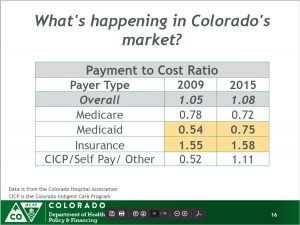

Data from the Department of Health Care Policy and Financing (HCPF) and the Colorado Hospital Association show that government health programs are not paying their way. Colorado’s Medicaid program pays 75 percent of its patients’ hospital costs. Medicare pays just 72 percent. People who pay for their own health care pay 158 percent (see graphic).

Advocates for low Medicaid reimbursements used to argue that Medicaid should pay only the relatively small additional costs hospitals incur by serving an extra person, costs for things like additional staffing, more laundry, and more drugs and disposables. Colorado Medicaid follows this approach because it lets it enroll more people for less. The problem is that someone else then has to cover overhead costs, things like paying for administrative staff, regulatory compliance, insurance, maintenance, and the capital cost of buildings and equipment.

Advocates for low Medicaid reimbursements used to argue that Medicaid should pay only the relatively small additional costs hospitals incur by serving an extra person, costs for things like additional staffing, more laundry, and more drugs and disposables. Colorado Medicaid follows this approach because it lets it enroll more people for less. The problem is that someone else then has to cover overhead costs, things like paying for administrative staff, regulatory compliance, insurance, maintenance, and the capital cost of buildings and equipment.

If patients on Medicaid are a small segment of a given hospital’s patient population, government underpayment has relatively little effect on the quality of care because their missing overhead contribution is relatively small. When Medicaid patients are a large segment of the patient population, underpayment means that hospital management struggles to match costs to revenues.

This leads to run-down hospitals with poor staffing and antiquated equipment.

In 1995, 1 in 13 Coloradans received some sort of aid from Medicaid. That was 294,000 people out of a population of 3.75 million. By the middle of 2016, 1 in every 4 Coloradans was enrolled in Medicaid, 1.33 million people out of a population of 5.54 million. In FY 2014-15, Colorado Medicaid’s acute care inpatient and outpatient hospital bill was $1.2 billion.

The Hospital Association says that hospitals shift the cost of low Medicaid reimbursement to private payers. But with 1 in 3 Coloradans enrolled in either Medicare or Medicaid, there are fewer people to shift costs to. In Costilla County, for example, an estimated 53 percent of the population is enrolled in Medicaid. Another twenty percent is enrolled in Medicare.

The academic evidence suggests that low payment and poor quality go hand in hand. Differences are large enough that quality differences between hospitals treating patients of higher and lower socioeconomic status, some of the so-called “racial disparities” in health care, might occur simply because so many Medicaid patients receive treatment in lower quality hospitals. Academic work on the subject even suggests that states that expanded Medicaid between 2010 and 2013 had more emergency department closures. Researchers speculate that hospitals did this in order to make their costs match Medicaid payments from Obamacare’s Medicaid expansion.

People who think expanding Medicaid to cover basically healthy people was good public policy will suggest raising taxes to fund higher hospital reimbursement rates. Unfortunately, there isn’t much evidence that those higher taxes will be used to pay for patient medical care. The British and Canadian health systems, both of which are funded with high taxes, still suffer from huge deficits, inadequate hospitals, and poor patient care.

More tax revenue doesn’t solve the problem because those who run government health programs don’t necessarily benefit from paying for patient care. In FY 2015-16 Colorado distributed $552.4 million in provider fee revenues to hospitals. Awards were based on hospital location, classification, volume, bed count, estimated Medicaid discharges, and estimated Medicaid caseload growth. Hospitals could receive money for things like Patient Family Advisory Council meetings, daily unit safety briefings, and handing out information on local primary care clinics.

Unlike payment for services rendered, none of these activities rewards hospitals for providing specific types of acute care to individual patients.

The best solution would be to increase the number of private payers in the state, while recognizing that government programs should actually pay for the medical services they use. This requires restoring Colorado’s market for health coverage so that people who want coverage for hospitalization can get policies that fit their budget. It will also require judicious Medicaid reform.

The main thing to remember is that if hospitals profit from treating patients well, they will continue to do so. If government actions make hospitals lose money for treating patients while allowing them to make money from holding government-sanctioned meetings and doing government-sanctioned busywork, they will do that instead.

Give bureaucrats control of the money and you get the Veterans Administration Health System or England’s National Health Service. Put control back into private hands and you get more direct pay primary care practices, and hospitals dedicated to taking care of patients.

Linda Gorman directs the Health Care Policy Center at the Independence Institute, a free market think tank in Denver.