By: Tegan Truitt

Sixth blog in our series on the Colorado Green New Deal

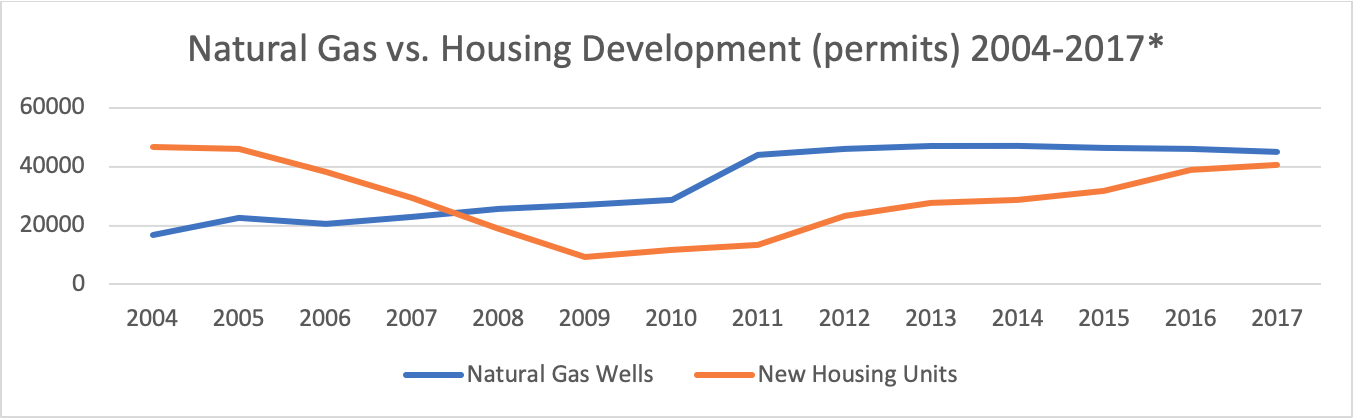

In Colorado, the number of natural gas wells tripled from about 17,000 in 2004 to around 40,000 by the end of 2017. Crude oil production also spiked in the same time frame, increasing from a meager 114,000 barrels in 2004 to 325,000 barrels in 2018. This expansion has prompted growing residential concern, and Democrat leadership in the General Assembly decided to take this issue on by introducing and passing SB 181, which comprehensively reformed the way in which Colorado regulates the industry.

One of the Democrats’ chief reasons for adopting 181 is the belief that the oil and gas industry has been encroaching into residential areas.

However, reviewing recent history reveals a different story, illustrating that it is not so much drilling that has encroached on housing as it is the other way around. The graph below depicts the number of drilling permits issued annually against the number of new housing permits issued annually. There is a sharp decline in residential expansion in 2009, likely a result of the 2008 financial crisis. Since the land was not otherwise employed, natural gas companies were able to buy it up.

*Data on natural gas wells from the Energy Information Administration. Data on new housing permits from St. Louis Federal Reserve.

The data suggests that after the expansion of drilling brought about renewed economic hope, residential building permits started to increase again. By 2017, Colorado’s population had ballooned, and housing was expanding at a much faster rate than natural gas extraction.

Colorado is thus witnessing not a conflict of greedy corporations against innocent homeowners, but instead a natural tension between two entities: a growing population that is starting to bud up against an industry that has been and still is a major player in the state.

It is worth mentioning though, that the rapid expansion of not only natural gas drilling but also oil production was a critical touchstone in drawing Colorado out of recession. The drilling boom helped facilitate Colorado’s recovery from the 2008 financial crisis, and thus likewise the housing boom.

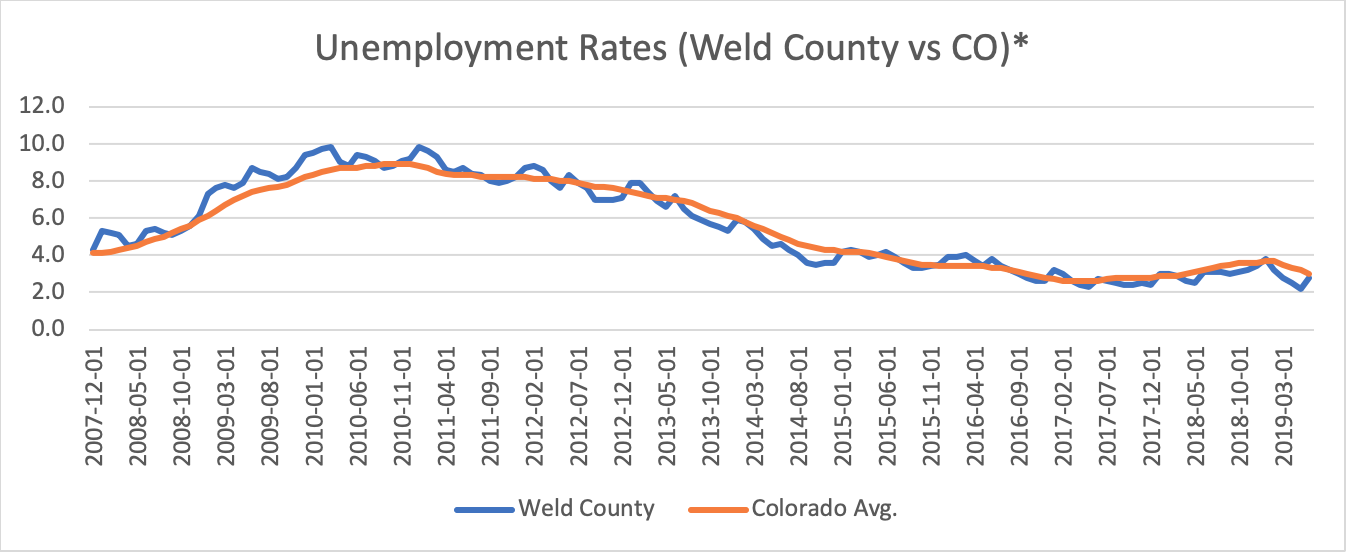

My case in point is Weld County, which was hit harder by the recession than most of the state. Unemployment there was at times almost two percentage points higher than the state average. But by 2012, its unemployment rate dropped below Colorado’s by an entire percentage point and remained lower until 2015, when the national unemployment rate stabilized between 2 and 3 percent.

What caused Weld’s astonishing early recovery? The oil and natural gas boom. All of Colorado benefitted, but Weld, which is located over a large shale deposit, was positioned to gain the most from the rapid expansion in the extraction industry.

* Unemployment rate for Weld County against Colorado’s as a whole – from 2008 to the present.

Data from Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (here and here).

Ironically, Weld County also acts as a case study for how to deal with the general public and extraction companies co-inhabiting the same locale, as they haven’t always gotten along. In 1992, Greeley even tried to outlaw fracking (the Colorado Supreme Court ultimately prevented this), and the recent boom has prompted concern over the proximity of oil rigs and extraction sites to residential areas. But fast forward to 2019, and residents and extraction companies co-exist – even happily at times.

The reality is, even with a semi-contentious relationship, the people residing in Weld value the presence of the industry, and not without reason. Oil and natural gas companies provide almost half of the county’s property taxes and make significant charitable contributions. Many recognize the myriad benefits the industry brings to the county. As one local put it, “I think it’s wonderful… It’s jobs, and it’s money.”

The industry brought about renewed economic life for northern Colorado – a blessing in a period of deep economic downturn. However, this renewed life, coupled with legislative reforms, attracted a rapidly growing population.

The oil and gas industry is native to Colorado; the conflicts with the industry come from new migrants to the state. This is not to say that Colorado should side with oil and gas – on the contrary, we should assimilate any who so wish into our Rocky Mountain way of life. Rather, we must recognize the industry is as much a part of this way of life as is hiking and skiing and Coors.

As its operations continue to expand, we should consider the lessons from Weld County. Extraction work can be an economic powerhouse; it lifted Northeastern Colorado out of dire financial straits and there is the very real possibility of successful – not flawless, but successful – extraction/residential cohabitation.

Waging war the industry, as the Democrats have done with SB 181, is not the answer. The property rights of both the land and mineral owners have to be respected. Hamstringing one party (in this case it’s the holder of the mineral rights) may be tolerated in Boulder, but it certainly won’t work for counties like Weld.

Tegan Truitt is an intern with the Energy and Environmental Policy Center. He is a rising junior at Grove City College, double majoring in economics and philosophy and minoring in math.

Colorado Green New Deal blog series:

Introduction (Blog Post 1), Blog Post 2, Blog Post 3, Blog Post 4, Blog Post 5, Conclusion