By Simon Lomax

Be afraid. Be very afraid…

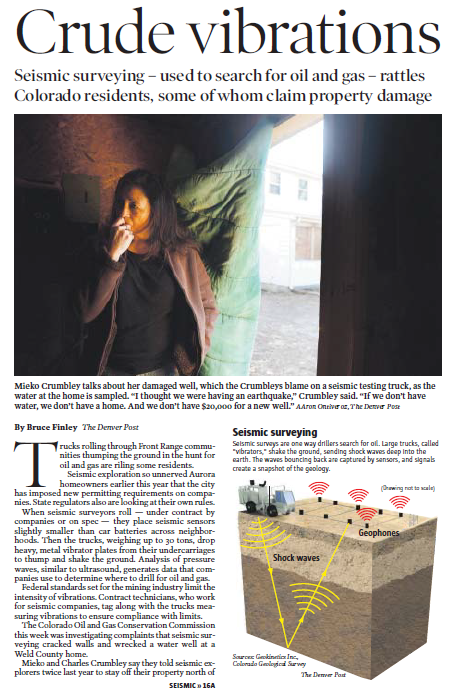

That was the Denver Post’s front page article on March 16, which profiled a couple – Mieko and Charles Crumbley – who claim seismic surveying near Brighton, Colo. damaged a groundwater well on their property and put cracks in some of the walls in their home. But the oil and gas company that commissioned the survey says its contractors did not cause the damage, according to the story by the Post’s environmental writer Bruce Finley. Sounds like one of those classic “he said, she said” situations, right?

Well, no, actually. In reality, the claims by the Crumbleys are very unlikely, based on readily available facts on the way seismic surveying works. But the reporter failed to include those facts, and painted a misleading and frightening picture for his readers.

The type of seismic surveying in question is carried out by vibroseis trucks, which are informally known as “thumper trucks.” The use of these trucks has greatly reduced the use of small dynamite charges in seismic surveying. Here’s how the reporter describes the way these vehicles work:

“[T]he trucks, weighing up to 30 tons, drop heavy, metal vibrator plates from their undercarriages to thump and shake the ground. Analysis of pressure waves, similar to ultrasound, generates data that companies use to determine where to drill for oil and gas.”

Sounds pretty ominous. But take a look at this video of some vibroseis trucks in action:

In fact, while these vehicles are unquestionably big, the vibrations they create are very small. For that reason, scientists with state and federal agencies, experts in academia, the geologists and engineers of the oil and gas industry, and even other media outlets have reaffirmed the safety of vibroseis trucks many times. Here are a few examples:

In an urban environment, vibroseis-generated waves are less than background noise generated by buses, trucks, and trains … At its source you can feel a vibroseis shake the ground but as you move away your ears will hear the airborne sound waves much longer than your feet can feel those in the ground.

Residents standing near a vibroseis truck … may be able to detect it, but this process will not cause any interruptions of daily life or damage to structures.

U.S. National Energy Technology Laboratory

Despite their relatively benign operations, these big machines sometimes appear more daunting to the populace than the commonplace dynamite. To assuage any concerns in that regard, companies sometimes resort to public demonstrations prior to operations. … Two light bulbs and two raw eggs were buried eight inches under the vibrating pads. Following the demo, the eggs were retrieved unbroken and the light bulbs still worked – to the amazement of the crowd of onlookers…

American Association of Petroleum Geologists

“If you stand near the truck you’ll be able to feel slight shaking in the bottom of your feet, but the level of shaking is far below the levels required to cause damage to pavement or structures” said [USGS scientist Rob] Williams.

The seismic imaging process does not damage the street or negatively impact the earth below ground.

Long Beach Post (Long Beach, Calif.)

[T]here is no reliable evidence of these trucks causing well problems or damage to buildings.

Unfortunately, the Post story didn’t just leave out these expert opinions. The article went a step further and suggested the Crumbley claim was one of several structural damage complaints. From the news story:

“State records show that since 2000, residents have filed 16 formal complaints about seismic surveys.”

Given the statements by the USGS, NETL and others about the very low risk of structural damage from vibroseis truck, we asked the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission to identify those 16 complaints, which include the Crumbley case. Then we reviewed the case files on the COGCC’s online database.

It turns out just three of the complaints allege any structural damage from vibroseis truck operations. The rest of the complaints mostly deal with disputes over property access, noise and the potential impact of these heavy vehicles on soil and crops. Besides the Crumbley case, there are no other complaints of damage to a house, and only two allegations of damage to water wells.

In the first water well complaint, from 2000, the COGCC concluded there was “no indication that oil and gas activities in this area impacted the well.” It turned out the well was located next to the burned-out shell of an old house, hadn’t been used in two years, and there was trash both around and floating inside the well. In the second water well complaint, from 2002, the COGCC found“no direct evidence of impact due to oil and gas operation” and concluded “[t]he most probable cause is corrosion in the casing from a shallow aquifer.”

So, instead of state records showing 15 other cases that support the Crumbley complaint, there appear to be none. Which makes sense, of course, because state and federal officials, industry experts and academics have repeatedly said that vibroseis trucks are very unlikely to cause structural damage.

However, let’s play the reporter’s game for a moment and assume the worst possible interpretation of those state records. Even when you group together all the 16 complaints to the COGCC that mention seismic surveying over the last 13 years – and include some more from residents in Aurora, Colo., as the Post’s story did – it’s hardly evidence of a commercial activity run amok. In fact, the Post’s own reporting suggests an average of between one and two complaints a year. That’s not bad when you consider Colorado’s oil and gas production has more than doubled since 2000. And it’s not scary either.

Of course, only time and further investigation will tell whether the Crumbley’s claims – however unlikely – are correct or mistaken. We’ll also have to wait and see if the alarmist tone of this particular news report scares some other residents into blaming seismic surveying for cracks in their drywall. But we can say two things now without equivocation: The oil and gas industry will cooperate fully with the state regulators investigating this matter, and the business of seismic surveying is nowhere near as scary as reporter Bruce Finley would have you believe.

This column appeared originally on Energy In Depth, a project of the Independent Petroleum Association of America as a research, education and public outreach program “focused on getting the facts out about the promise and potential of responsibly developing America’s onshore energy resource base.”

For a well-researched, easy-to-read, factual primer on hydraulic fracturing, check out our paper Frack Attack: Cracking the Case Against Hydraulic Fracturing.