By Rob Natelson

Author’s note: I’ve divided most of my adult life between my two favorite states, Colorado and Montana. The histories of the two states are intertwined in intriguing ways. This article, first published in the Missoulian newspaper, tells how Montana received a name initially applied to places in Colorado.

# # # #

How did Montana come to be called Montana? Here is the story.

Contrary to what you may read elsewhere, the word “Montana” is not Spanish. The closest Spanish word is montaña”—meaning “mountain” and pronounced “mon-TAHN-ya.” Montana is a Latin adjective meaning “mountainous.”

The notion of Spanish origin has been promulgated by writers apparently unfamiliar with either Spanish or Latin. Historian Wilbur Edger Sanders, for example, suggested the word was Spanish although the circumstances he describes point clearly to a Latin derivation. That Latin derivation was to prove important.

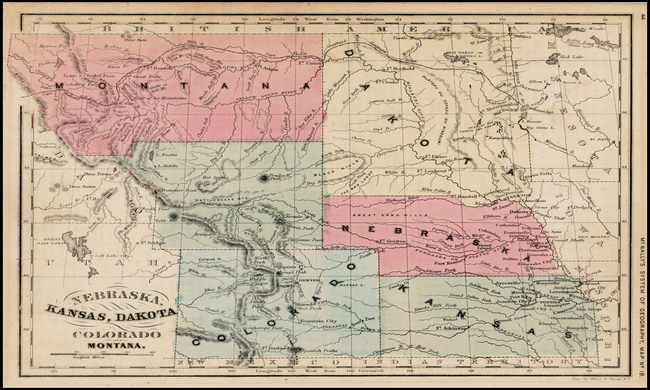

The Territory of Kansas initially included a chunk of east-central Colorado called Arapahoe County. In 1858, gold miners established the first organized Arapahoe County town, located near present-day Commerce City, Colorado. One of their number, Josiah Hinman, a college graduate—who like all contemporaneous college graduates had studied Latin—suggested they call their settlement “Montana.” They agreed.

The following year, the Kansas Territorial legislature voted to split Arapahoe County into several parts, one of which was to be Montana County. It comprised what is today the City of Denver and the area to the west and southwest. In 1860, miners in far western Kansas (now Clear Creek County, Colorado) opted to designate their settlement “Montana.” When Colorado Territory was organized in 1861, some wanted to call it by the same name.

But the two towns named Montana died away, Montana County was never organized, and Colorado became Colorado. (The present state of Kansas does include a hamlet named Montana.)

James W. Denver, who served as Kansas territorial governor, reportedly suggested “Montana” to Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas as a potential label for a future territory. Douglas passed the idea to James M. Ashley, a self-educated Ohio Congressman later notable as sponsor of the 13th amendment, which abolished slavery.

Ashley was on the House Territories Committee. Early in 1863 he introduced HR 738, whose first draft would have designated as “Montana” a vast new federal territory comprising modern Idaho, Montana, and most of Wyoming. The proposal passed the House, but during Senate deliberations Benjamin F. Harding of Oregon argued that “the name of Idaho is much preferable to Montana. Montana, to my mind, signifies nothing at all. Idaho, in English, signifies ‘the gem of the mountains’.”

The Senate agreed with Harding, the House concurred, and the new territory became Idaho.

Ashley did not give up. The following year he sponsored HR 15 to split the new territory into smaller portions. One portion followed Montana’s current boundaries, and Ashley proposed naming it “Montana.” His bill passed the House on March 17, 1864 and moved on to the Senate.

In the Senate, HR 15’s principal supporter was Jacob M. Howard of Michigan—subsequently famous as the leading Senate spokesman for the 14th amendment. Once again, some Senators resisted using the name Montana. Charles Sumner of Massachusetts declared, “The name of this new Territory—Montana—strikes me as very peculiar. I wish to ask the chairman of the committee what has suggested that name? It seems to me it must have been borrowed from some novel or other.”

This time, supporters were prepared, as the records of the debate show:

Sen. Howard: I will say to the Senator from Massachusetts that I was equally puzzled when I saw the name in the bill, and I labored under the same difficulty which my honorable friend from Massachusetts seems to be in. I was obliged to turn to my old Latin dictionary to see if there was any meaning to the word Montana, and I found there was.

Sen. Sumner. What was it?

Sen. Howard: It is a very classical word, pure Latin. It means a mountainous region, a mountainous country.

Sen. Benjamin Wade: Then the name is well adopted to the Territory.

Sen. Howard: You will find that it is used by Livy and some of the other Latin historians, which is no small praise.

Sen. Wade. I do not care anything about the name. If there was none in Latin or in Indian I suppose we have a right to make a name; certainly just as good a right to make it as anybody else. It is a good name enough.

So the resistance faded, and Montana became the name of the new territory.

Incidentally, Senator Howard was correct: “Montana” does occur in Livy’s magnificent Roman history: In book 19, Livy writes of loca montana—“mountainous area.” And I have frequently found the word gracing the beautiful Latin poetry of Virgil and Ovid.

As Senator Wade observed: The name is well adopted to the territory.